A food system under stress

An exceedingly worrisome trend has come into focus in the past few years. The slow, steady progress against hunger that had been a feature of the world economy for decades came to a halt during the pandemic, and it has not resumed.

Global poverty, in its severe forms, is characterised most starkly by hunger — or in more technical terms, by food insecurity. That phrase is defined as people lacking regular access to enough nutritious food to permit normal human development.

Figure 38: Living in poverty

This chart shows the number of people in each region living in extreme poverty, currently defined as an income of less than $2.15 per person per day.

Source: World Bank

In 2019, hunger afflicted about 7.5 percent of the world population. As the pandemic gripped the world in 2020 and 2021, that number jumped above 9 percent and has remained so, driving an estimated 152 million1 additional people into hunger. Not only did the pandemic disrupt economies, but the Russian invasion of Ukraine followed closely on its heels, shutting off Ukrainian grain exports and sending world food prices to record highs. Ukraine has lately opened a corridor and resumed some exports, but neither prices nor hunger have fallen all the way back to 2019 levels. At this rate, the world community is on track to fail at one of its major development goals: ending malnutrition by 2030.

Figure 39: Food prices are high

This chart shows that world food prices spiked during the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine, and have not fully returned to their previous level. The global Food Price Index is an average of the prices of 95 commodities tracked by the Food and Agriculture Organisation, weighted by export shares and adjusted for inflation.

Source: FAO

What is the connection between world hunger and the environmental crisis?

A growing body of research suggests that the rise in extreme heat waves around the world may be cutting into crop production, compared to what it would be without the increasing heat.2 In other words, while production is still rising — and it has to, with a net increase of 70 million new mouths to feed every year3 — it may not be rising as fast as it could without global overheating. However, there may also be a more acute, near-term linkage between heat and hunger. Recent research shows that severe heat waves can directly cut the income of outdoor workers. For example, construction projects in India often pay their workers — typically women — to carry loads of bricks, and they are paid by the brick. Similar conditions apply for farm workers paid by the basket for the fruits or vegetables they harvest. If heat waves force these workers to slow down or stop work, they lose income immediately, and may then be unable to buy enough food for their families.4

Hunger in Africa

More than any other part of the world, Africa is still stalked by hunger and malnutrition. Here, a feeding program called the Joseph Project serves children in the village of Buli in Malawi.

Source: Stephen Dorey ABIPP/Alamy

Figure 40: Where is hunger concentrated?

Hunger levels are highest in parts of Africa and southern Asia. The graphs represent the percentage of the population in each region suffering from moderate or severe food insecurity, a broader measure than the figures cited earlier in this chapter.

Source: UN

The global food system is a vast subject, and fully critiquing it is beyond the scope of this report. But some aspects of it bear directly on the world’s two major environmental problems — global overheating and the loss of biodiversity — so we will briefly recap some of the main issues.

Humans now use 38 percent of the world’s land surface to produce food.5 Immense regions of forest have been cut down and converted to agricultural use. While much of this land conversion occurred in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it continues at a slower pace, with forests in the tropics bearing the brunt of direct human assault these days. That, in turn, is helping to drive the extinction of large numbers of species that can live only in tropical forests, the richest ecological zones on the planet.

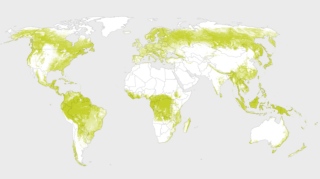

Figure 41: Plowing the Earth

This chart shows the amount of land converted to farming or grazing since 1700. The Asia category includes the European part of Russia, west of the Ural Mountains.

The tragedy is that much of the land that has been converted to farms is not very productive — meaning humans are using far more land than we need in order to produce a given amount of food. This ‘yield gap’ is stark, with millions of hectares across Africa, Asia and parts of Eastern Europe producing below their potential. The reasons are no mystery: many poorer farmers lack the basic agricultural inputs, such as fertilisers, pesticides and mechanical irrigation, that are common in the developed world. Conversely, in many middle-income countries that have developed intensive agriculture, including China and the Punjab regions of India and Pakistan, fertilisers are being overused, poisoning streams and creating ‘dead zones’ at the mouths of more than 700 rivers around the world. (Generation has invested in a company, Pivot Bio, that uses micro-organisms to help plants pull nitrogen out of the air, cutting the excessive use of chemical fertilisers.)

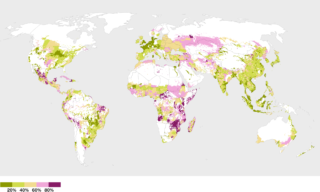

Figure 42: The yield gap

The redder an area on this map, the more agriculture there is lagging. The map shows the percentage by which production in a given area, in 2010, fell below the maximum achievable yield. The most negative value is 100%, whereas a value of 0% would mean that the best possible yield was achieved in that area.

The entire food system is more tenuous than many people realise. Most of the world’s land is in the Northern Hemisphere, and so most of its food is grown there; heat waves or other weather disasters afflicting broad swaths of that hemisphere can have a serious effect on the food supply. There is no vast global storehouse of extra food tucked away in a mountain somewhere; we live more or less from year to year. Governments have a tendency to lose focus on the food system, which means we are usually not spending enough on agricultural research — but then they rush in with extra aid when a crisis erupts. We are now in the middle of such a cycle, with the Group of 7 wealthy nations promising in June to unleash a new wave of agricultural finance. Italy has led the push, having come to understand that some of the migration straining Europe has been caused by food insecurity in Africa. Details of this new program — and, in particular, the exact amount of new money the rich countries will commit — have yet to be announced.

The expansion of agriculture onto new lands is a major reason for the world’s biodiversity crisis. If we want to salvage what is left of the natural world, then this expansion needs to stop immediately, worldwide. The priority needs to be on using existing farmlands more efficiently, and eventually withdrawing from many of those lands to return them to the wild.

This imperative puts the wealthy countries in an uncomfortable position: exhorting poor, developing countries not to destroy their forests the way the rich countries did many decades ago. Diplomats have long recognised that justice demands that poor nations be paid to keep their forests standing, but promises that tens of billions of dollars a year would be raised for this purpose have gone unfulfiled. This failure to finance the conservation of nature is one of the world’s fundamental injustices.

In terms of greenhouse gases and biodiversity loss, the costliest form of agriculture is the production of meat. Demand for meat keeps rising as incomes go up, ameliorated to some extent by a shift away from inefficient beef to more efficient chicken. Political leaders have been terrified of trying to engineer changes in people’s diets, but holding down the growth of meat consumption would go a long way toward easing pressure on the food system and the climate.

The subsidy schemes that have grown up in Western countries are among the biggest problems: they mainly support commodity agriculture, particularly the meat system, and do almost nothing to encourage the production of healthier foods or a shift to plant-rich diets.

One of the world’s most important experiments in agricultural subsidy reform is under way now in Great Britain. It is one of the only benefits we have been able to see from that country’s exit from the European Union. Liberated from the complex subsidy system run by the EU, Britain is reorientating its subsidies, paying farmers to adopt sustainable farming methods and to make more judicious use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides. The program is in its early stages, but we are hopeful Britain will pioneer new approaches that can be applied worldwide.6

Another possibility for cutting the environmental harm of agriculture is the development of meat alternatives: either plant-based meat lookalikes or, more exotically, actual meat cells grown in bioreactors. This sort of lab-grown meat is already being blended in small quantities into substitute chicken products that have reached the market in Singapore, but the technology is still costly, and broader use of lab-grown meat may still be a long way off. Plant-based meat products like the Impossible Burger and others are already on the market, of course, but public uptake has stalled, and investment in these approaches has been lagging for the last few years. We think some production breakthroughs are needed: the products need to get better, and most importantly, the prices need to come down so that meat substitutes are cheaper than meat itself.

Figure 43: Lagging investor interest

This chart shows investment in alternative methods of producing meat or meat substitutes. Investor interest has waned as consumer uptake of new products has slowed down.

Source: Good Food Institute

In regard to the world’s land, the single most urgent imperative now is to halt the ongoing destruction of tropical forests. We have fresh evidence of how big a difference political leadership can make on that issue.

Under the right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro, who governed Brazil from 2019 to 2022, the rate of destruction of the Amazon forest soared. His successor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, took office in 2023 vowing to restore law enforcement in the forest and cut the rate of illegal destruction.

The figures for calendar year 2023 show a 50 percent drop in deforestation in the Amazon compared to the previous year.7 Indonesia is another case where dramatic progress has been made in cutting deforestation through actions of the central government, an achievement that will stand as a major legacy of outgoing President Joko Widodo. We hope the incoming administration of Prabowo Subianto, who takes office in October, will prove to be as committed to forest protection as its predecessor.

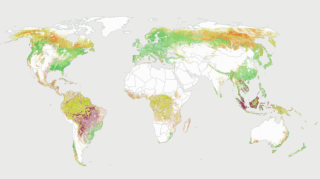

Figure 44: What's destroying the world's forests?

Forests are under stress worldwide, mostly from human activities. Pulling the slider on this map to the left will show the primary causes of forest loss in different regions. The expansion of commercial agriculture leads to large-scale, commodity-driven deforestation. Loss from ‘shifting agriculture’ is generally driven by small- to medium-scale farming and may be temporary. Loss from forestry occurs when natural forests are destroyed for commercial tree plantations. Wildfire losses are often natural and temporary, though human-caused global heating seems to be driving an increased loss of boreal forests in Canada and Siberia.

Source: Global Forest Watch

To be clear, the world is still losing tropical forests at an alarming rate, a profound threat to the long-term survival of the richest and most diverse ecosystems on the planet. A flurry of forest destruction is going on in Bolivia, a small country next to Brazil that shares part of the Amazon with it. Much of the destruction is not even against the law: Bolivia’s rapid embrace of industrial agriculture has led the country’s central government to authorise extensive forest clearance. A rising hotspot of deforestation is the Congo basin in Africa, where trees are being cut down largely by subsistence farmers. That war-torn region desperately needs better economic opportunities if the forest there is to survive.

Figure 45: When and where trees are dying

In the Northern Hemisphere, large stretches of boreal forest are being lost to fires made more likely climate change. These trees may ultimately grow back. Fires are also a problem in the tropical forest belt that spans the globe, but the bigger losses there are due to the expansion of agriculture.

Source: Global Forest Watch

The forest situation is yet another example of promises made but not kept. In 2014, 37 governments joined scores of businesses and many other organisations to sign the New York Declaration on Forests, vowing to cut deforestation at the global scale in half by 2020 and to end it by 2030. The first part of that commitment did not happen, and the second part is not on track to happen. Clearing forests and converting the land to agriculture remains profitable. Many of the products of deforestation still end up in the cupboards of Western shoppers.

The European Union is attempting, at last, to put a stop to the trade in such products within its borders. A new regulation went into effect in the middle of 2023, making it illegal to import into the EU products derived from commodities produced on deforested land. The commodities covered by the regulation are cattle, coffee, cocoa, palm oil, soybeans, wood and rubber. That may seem like a short list, but the consumer products potentially derived from those commodities are numerous: paper, books, tyres, soap, cosmetics, leather, furniture and many more. It remains to be seen, of course, how well the EU can enforce this regulation and how much pressure it creates for global corporations to clean up their supply chains, but we are hopeful this pioneering law will help to slow the loss of forests.

Controversy continues to swirl around another approach to helping forests: the sale in a $2-billion-a-year voluntary market of ‘carbon offsets,’ with the money often spent on projects meant to limit deforestation on particular plots of land. The credibility of many of these offsets has come into question in recent years, and efforts to clean up the marketplace are under way. A major new aspect to the controversy erupted earlier this year, when the Science Based Targets initiative, which certifies corporate climate plans, announced that it might start allowing the offsetting of certain emissions through the purchase of such certificates. That set off internal turmoil at the organisation, but it now seems poised to allow only limited use of the highest-quality offsets.

- 1. This number is of course an estimate, with error bars. The United Nations agencies that monitor world hunger calculate that 713 million to 757 million people faced hunger in 2023. Comparing the midpoint of that range to the midpoint of the 2019 estimate yields the figure of an additional 152 million hungry people since the pandemic. See FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, 2024: “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 — Financing to End Hunger, Food Insecurity and Malnutrition in All its Forms.” Back to inline

- 2. Zhao, Chuang et al, 2017: “Temperature Increase Reduces Global Yields of Major Crops in Four Independent Estimates.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114 (35), 9326 – 9331. Back to inline

- 3. This figure is simply the size of the birth cohort, currently estimated at 132 million a year, minus estimated deaths of 62 million a year. See Our World in Data: “Births and Deaths Per Year, World,” retrieved August 2024. Back to inline

- 4. Kroeger, Carolin, 2023. “Heat is associated with short-term increases in household food insecurity in 150 countries and this is mediated by income.” Nature Human Behaviour 7, pp. 1777 – 1786. Back to inline

- 5. Food and Agriculture Organisation, 7 May 2020: “Land Use in Agriculture by the Numbers.” Rome. Back to inline

- 6. For details of the British scheme, see Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs, 21 June 2023: “Environmental Land Management Update: How Government Will Pay for Land-Based Environment and Climate Goods and Services.” This policy paper was published by the Conservative-led government that was voted out of office in July, but the new Labour government seems to want to retain most aspects of the policy. Back to inline

- 7. MAAP Project, 2023: “Amazon Deforestation and Carbon Emissions.” Back to inline